Tempered By Time

From the beginning of the 20th century until well after World War II, Switzerland commanded over 90 per cent of the total sale of mechanical watches sold around the world. Their craftsmanship, attention to detail and the fine art of watchmaking were (and continue to be) respected by collectors everywhere.

In 1969, Japanese brand Seiko launched the world’s first quartz watch - the Astron - which measured time with a gain or loss of under five seconds a day. The world took notice. Interest in the craft of mechanical watchmaking dwindled and attention to timing and precision increased. This ‘quartz crisis’ as it was called, further fuelled by the release of digital display watches, would in turn cause a debilitating collapse of the Swiss watch industry.

Seen above are the World’s first quartz watch, a six-digit LCD watch and a multi-function digital watch from Seiko, released in the years 1969, 1973 and 1975 respectively. Image Credit – Seikowatches.com

Massive losses in sales and with over 90,000 employees retrenched; the industry was neck deep in a quicksand - Switzerland’s worst economic crisis. Ironically, the first ‘made in Switzerland’ quartz movements like the beta 21 were first used by brands like Patek Philippe, only to fall victim to poor sales and few takers.

Nicolas Hayek and Jean Claude Biver to the rescue

It took two entrepreneurs - Nicolas Hayek and Jean Claude Biver - to tactically revive the dying Swiss watch industry with their eye for game-changing mergers.

In 1981, Jean Claude Biver, a young manager-turned-entrepreneur from Switzerland bought over fast failing Blancpain, completely restructuring the marketing of their mechanical watches to promote hand-crafted movements as an age-old tradition worthy of being cherished and unworthy of being forgotten. He set the precedent for several other watch manufacturers to continue to believe in their craft of making mechanical watches and not give up in the face of the overwhelming quartz crisis that had hit them all.

Jeane Claude Biver , now Ceo of Tag Heuer, along with the team at LVMH. Image Credit – calibre11.com

At the age of 57, Nicolas Hayek was instrumental in uniting two of the largest Swiss watch groups - the Allgemeine Gesellschaft der Schweizerischen (ASUAG) and the Société Suisse pour l'Industrie Horlogère (SSIH) groups - thus creating the Swatch Group in 1985 that is now best-known for their slimmer, cool and colourful quartz watches with psychedelic dials that cater to the tastes of youngsters the world over.

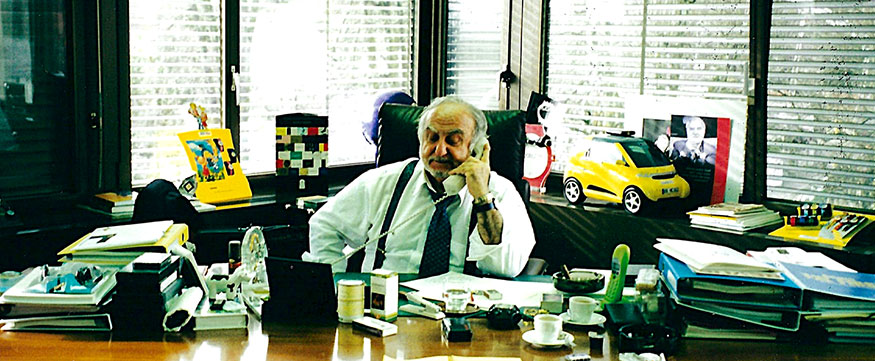

Nikolas Hayek in his Swatch Group office, wearing a Swatch watch, on a Swatch telephone, with a model of the Swatch-mobile along with another Swatch phone on the desk. Image Credit – Hodinkee.com

Meet Charles Vermot and Edmond Capt.

While the aforementioned men were an integral part of the Swiss industries’ rich heritage and history, the next two are those who went above and beyond the call of duty to save years of research that would only bear fruit much later.

In 1964, Zenith, one of the world’s leading manufacturers of pocket and wrist watches began to play with the idea of creating the world’s first fully integrated automatic chronograph. Chronograph mechanisms up to that point were built as an addition to the already existing base movements of the watch. Watchmaker Charles Vermot and his team were tasked with this.

In 1969, following the culmination of half a decade of research, planning and development, Zenith released their chronograph movement and aptly named it the ‘ El Primero’. Charles Vermot and his team had successfully built a movement where the stopwatch would be part of the time measuring movement, along with a day and date function and a running seconds to measure time up to 1/10th of a second.

Charles Vermot and quite possibly the greatest chronograph caliber of the early 70s, the mighty El Primero.

Zenith’s big success came when the Rolex Cosmograph Daytona watch (a watch highly sought after today) used a heavily modified version of the El Primero chronograph movement upto the year 2000 till they transitioned to their own in-house caliber.

But when the quartz crisis hit in the early 70s, around a year after the release of the El Primero movement (which we discussed earlier), Zenith decided to abandon this movement and re-invest in making quartz movements. Charles Vermot was asked to shut shop and sell all the tools and machinery connected to the development of the El Primero. However, he didn’t do so, hiding away all his work in the company’s attic, where it collected dust for over 10 years. When the Swiss mechanical watch industry was ultimately revived, Vermot’s foresight enabled Zenith to release several thousand El Primero movements to brands to build automatic chronographs. Rolex, as mentioned above, signed a contract with Zenith to buy the El Primero caliber for the next 10 years.

The first Zenith El Primero A384 model along with the infamous attic where Charles Vermot hid all material related to its creation.

Looking back, Vermot’s decision not to write off the El Primero was one of the most momentous moments in watchmaking.

Another story, barely 50 kilometres from the Zenith factory, concerns movement manufacturer Valjoux, and is a tale of foresight and perseverance much like Vermont’s. Edmond Capt and his team were asked to develop a robust chronograph movement with a quick set day and date, which would be relatively easy to manufacture. The finished movement was called the Valjoux 7750.

Just like Vermot at Zenith, Capt too was told to stop work on the development of his movementAll drawings and tools were to be destroyed during the very same quartz crisis. But Capt did no such thing. He hid all tools and drawings related to the Valjoux 7750 in the buildings of Valjoux, making rounds at night, walking surreptitiously past security guards to carry on his research.

Edmond Capt beside the Valjoux caliber 7750. Image Credit – awci.com

Several years later in the ’80s, with the resurgence of the Swiss industry, this well-guarded material saved the company years of research by helping them produce the 7750 on a large scale for Breitling, IWC and many more. Today, modified versions of the 7750, either stripped down or built up, are used by IWC, Breitling, Omega, Longines, Panerai and Hublot among others.

I wrote this blog to pay homage to men who fought hard to keep their dreams and their industry alive. Two men who worked from the outside, combining brands and entire organisations to hold strong on the horological battlefront. And two master watchmakers whose foresight and commitment to their own creation, which today, stand as the base of thousands of watches and are the very foundation of the chronograph in the Swiss watch industry.